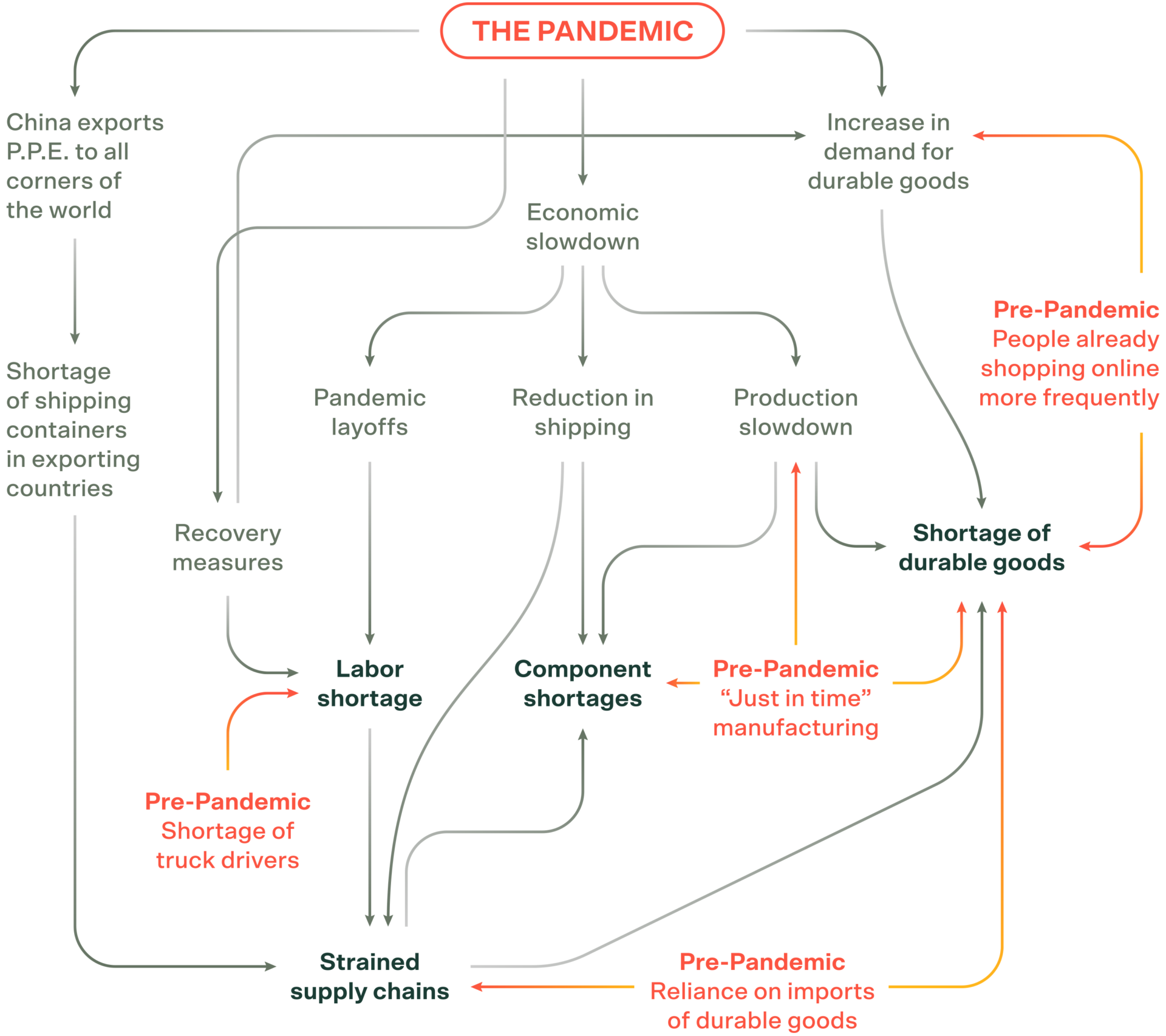

In early 2020, countries across the world went on lockdown. Billions of people were quarantined in an effort to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus. Subsequently, supply chains across the world began suffering disruptions that have yet to be resolved.

Today, the price of gas, construction materials, consumer electronics, and even real estate is still increasing because of these supply chain disruptions. And while many might like to blame COVID for our current economic crisis, the fact is that COVID isn’t really responsible.

In fact, there are many other causes of this current crisis. Most of these have been building up for years, but little effort was done to fix them.

For example, “just in time” manufacturing, increases in online shopping, shortage of delivery drivers, and the excessive reliance on the importation of foreign goods were all pre-pandemic supply chain vulnerabilities.

How the COVID19 Pandemic Exacerbated Pre-Pandemic Supply Chain Issues. Source: New York Times

While these vulnerabilities were kept under control for many years — and, in some cases, decades — it was only a matter of time before a major global event, like the coronavirus pandemic, catalyzed major supply chain disruptions.

In this article, we look at how the pandemic exacerbated pre-pandemic supply chain issues in order to help you understand the real causes of failing supply chains that affect people just like you and me.

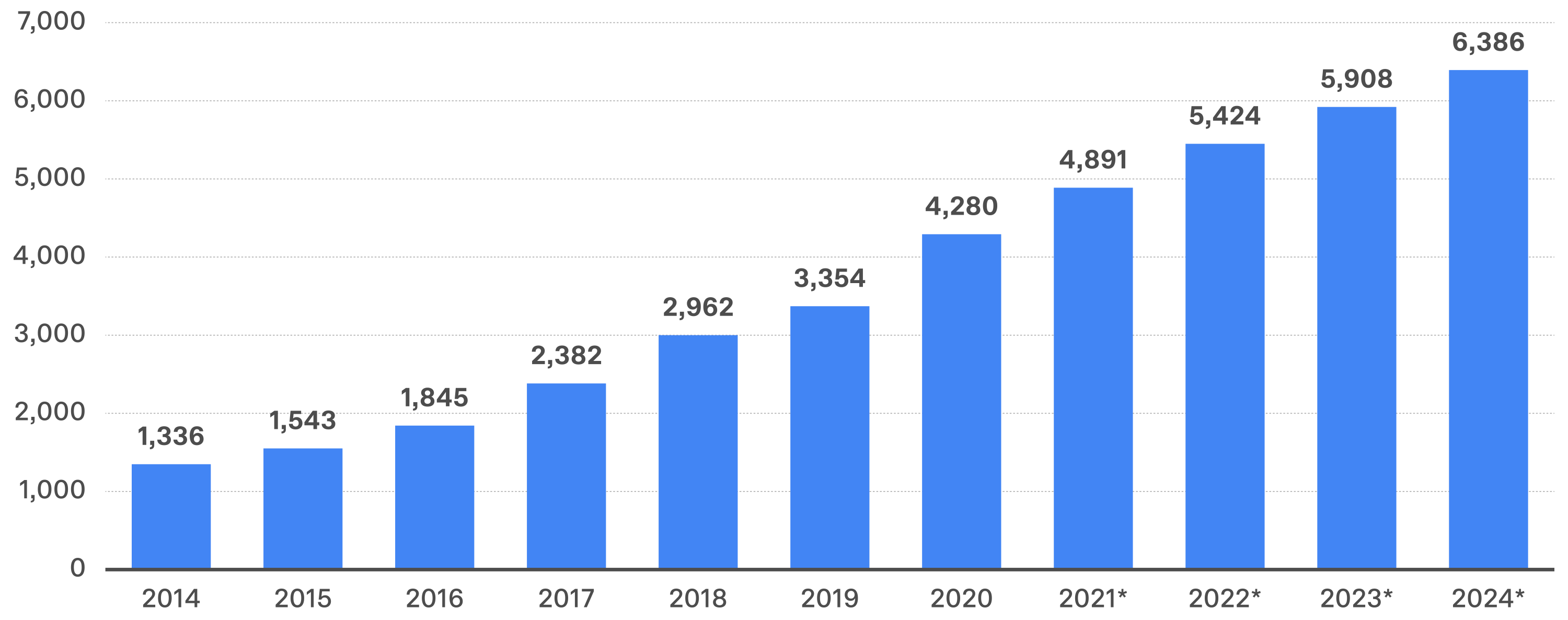

Online Shopping Before and After the Coronavirus Pandemic

Well before the pandemic began, online shopping was already on the rise. Between 2014 and 2019, global e-commerce retail sales jumped from just under 1.34 to over 3.35 trillion dollars, an increase of over 150%.

Increase in retail e-commerce sales worldwide from 2014 to 2024 (actual and projected) Source: International Trade Administration

The largest increase during this period was between 2016 and 2017, when sales increased by over 29%. Subsequent years saw a drop-off in growth with sales rising by around 25% between 2017 and 2018 and just under 12.5% between 2018 and 2019.

Comparatively, during the first year of the coronavirus (2020), sales skyrocketed with an increase of over 27% compared to the previous year (2019). While this was quite a leap, the rise between 2016 and 2017 was technically larger.

Thus, the increase in online shopping associated with the coronavirus cannot be considered the sole cause of current supply chain disruptions — though it is certainly a contributing factor.

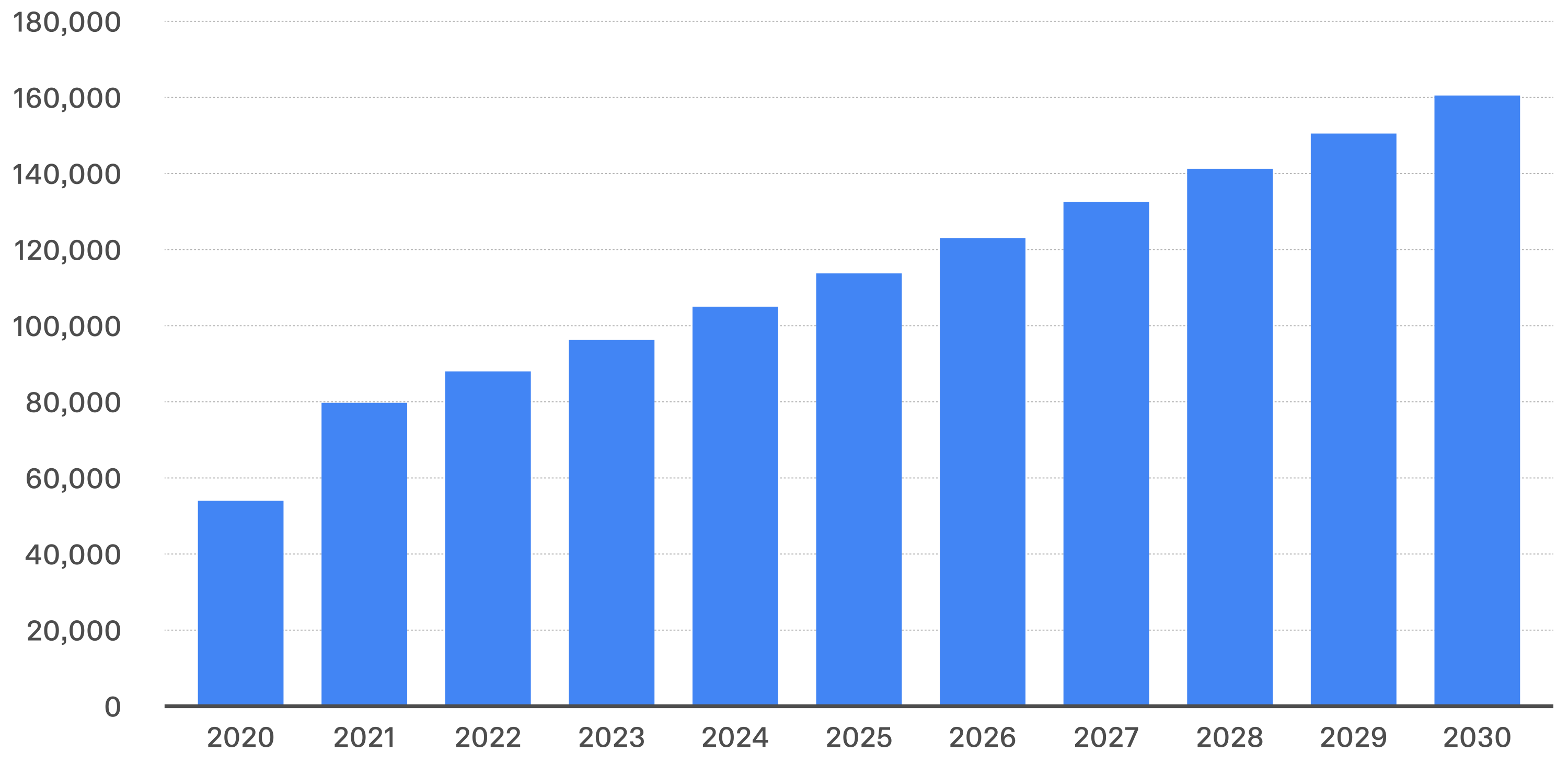

Truck Driver Shortage Existed Long Before COVID

Another cause of the current disruptions is the lack of truck drivers available to deliver goods to customers. If there was a sufficient supply of drivers, then many domestic supply chain vulnerabilities might be easily resolved.

In May of 2018, the Washington Post reported that there was a shortage of 51,000 drivers at the end of 2017, an increase of 36,000 from the year prior.

Long before the coronavirus emerged, the trucking industry was trying — and failing — to solve this problem.

Higher wages, signing bonuses, and regular raises have proven unsuccessful. In fact, according to a Driver Update Shortage from the American Trucking Associations released in October of 2021, the truck shortage is only expected to get worse.

In 2021, there was a projected shortage of 80,000 drivers. By 2030, this number is expected to double. Source: American Trucking Associations

Within the report, 8 causes of the shortage are listed. Only 1 references the coronavirus pandemic, noting that the pandemic caused some turckers to leave the industry while forcing truck driver training schools to train fewer drivers in 2020 than in previous years.

Other issues cited include:

- High average age of truck drivers

- The truck driving lifestyle

- Must be 21 years to earn a commercial interstate trucking license

- Few attempts to recruit women

- Legalization of marijuana in multiple states correlates to fewer people being able to pass a drug test, a requirement for driving trucks

In other words, the truck driving industry knows that it has a problem, but it doesn’t appear to know how to fix it.

“Just In Time” Manufacturing — A Poor Economic Model for Global Supply Chains

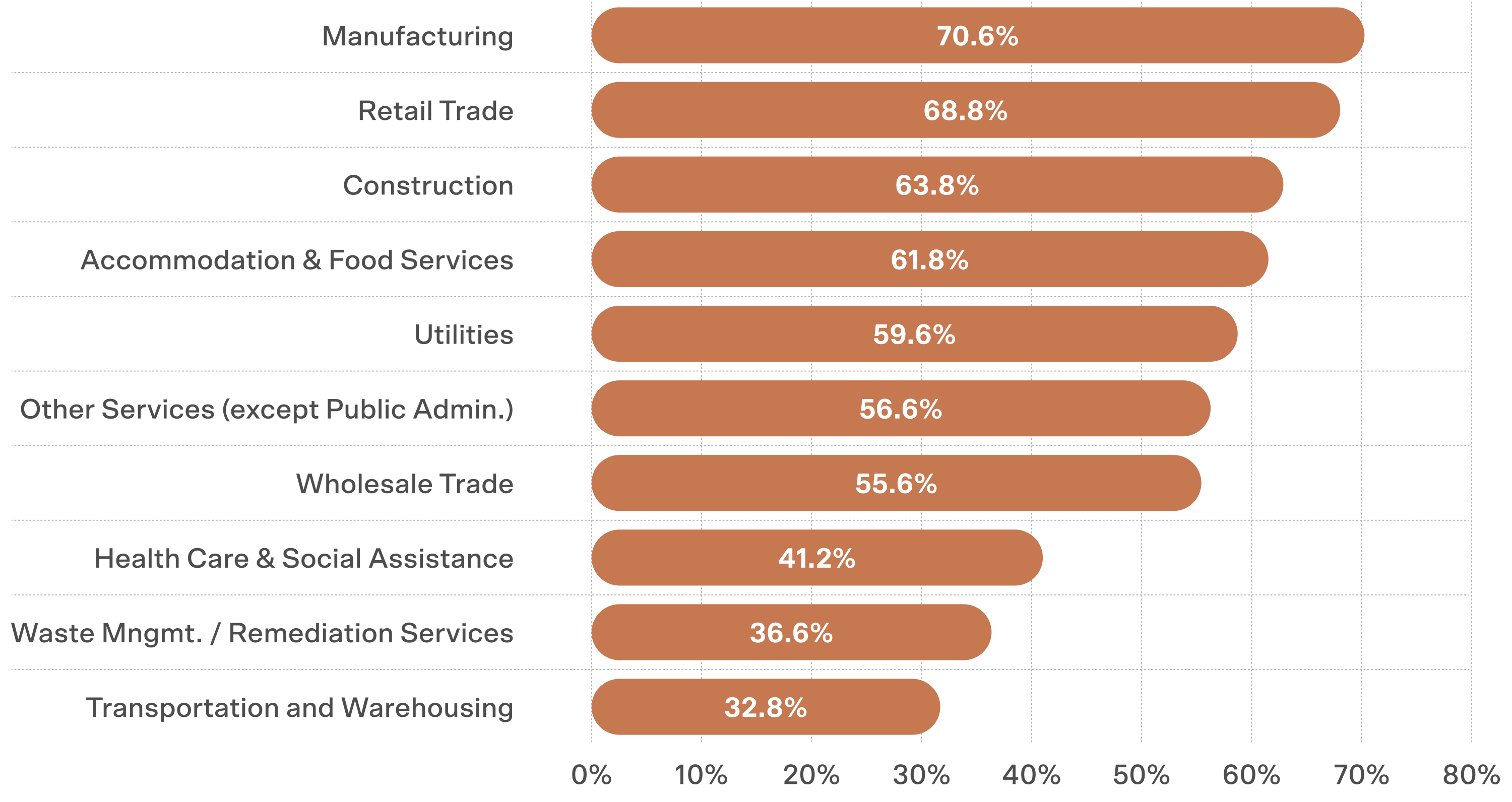

Since the start of the pandemic, the industry most affected by supply chain issues has been the manufacturing industry. During the week of January 10 to 16, 2022, over 70% of US small businesses within the manufacturing industry reported domestic delivery delays.

Furthermore, industries that rely on the production, distribution, and sale of manufactured goods have suffered similarly as seen in the chart below:

Top 10 Industries Reporting Domestic Delivery Delays By Percentage (01/10/22-01/16/22) Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Small Business Pulse Survey

Online shopping and truck driver shortages may be partly at fault, but the biggest reason why manufacturing is suffering so heavily is because of the “just in time” or lean manufacturing model that many businesses rely on to save costs associated with overproduction and excessive labor.

The Self-Destructive Logic of Lean Manufacturing

The purpose of lean manufacturing is simple:

Produce only what is needed when it is needed.

A key component of lean manufacturing is to reduce or eliminate inventories by creating and monitoring supply chains with careful precision. Every resource, component, and good that is manufactured is only produced when there is a known demand for it.

Thus, this model demands an equilibrium between supply and demand that does permit stockpiling. As long as this balance is maintained and demand remains within expected ranges, JIT functions well.

However, when there is a sudden shift in demand or labor, the JIT model becomes self-destructive. Without inventories, spikes in demand or substantial losses in the labor force create situations in which goods cannot be produced or delivered quickly enough.

The Coronavirus Proves “Just In Time” Manufacturing is Not Fast Enough

Throughout the pandemic, demand for manufactured goods — especially consumer electronics — skyrocketed.

Not only did personal online shopping increase demand, but the shift to remote and hybrid work required businesses and individuals to acquire new computers, phones, headsets, webcams, and other similar items in order to continue working.

Without adequate inventories of these items or the resources and components needed to produce them, the JIT model began to collapse.

This collapse has been worsened by the ongoing truck driver shortage. Even if there were sufficient supply to meet customer demand, the goods still have to be delivered to the consumer. And without enough drivers, items cannot be delivered.

Furthermore, the massive layoffs during the early days of the pandemic halted the production of all manufactured goods throughout the world. Even though lockdowns aren’t as common, labor shortages persist as production and service workers continue joining the Great Resignation en masse.

A Final Word On Lean Manufacturing and the Need for Inventory

The simple truth is that the JIT model was never an adequate model for global supply chains. It was only a matter of time until a global event fundamentally shifted the balance of demand, supply, labor, production, and delivery to a point of massive disruption.

If it wasn’t the coronavirus pandemic, it would have been something else. As we are now learning, even the most well-monitored and maintained supply chains are still incredibly fragile and can be disrupted at any time.

Reliance on International Trade Has Always Been a Global Problem

International trade brings many benefits. With lower labor and manufacturing costs in foreign nations, businesses save money while expanding the diversity of products available to customers.

However, an overreliance on international trade brings substantial risk — especially when lean manufacturing is implemented within the supply chain as it requires businesses to reduce or eliminate surplus inventory while ensuring supply is capable of meeting global demand.

This is difficult, if not impossible because unpredictable social events like nationalized protest movements, regional strikes, or global pandemics can quickly throw the entire system into chaos.

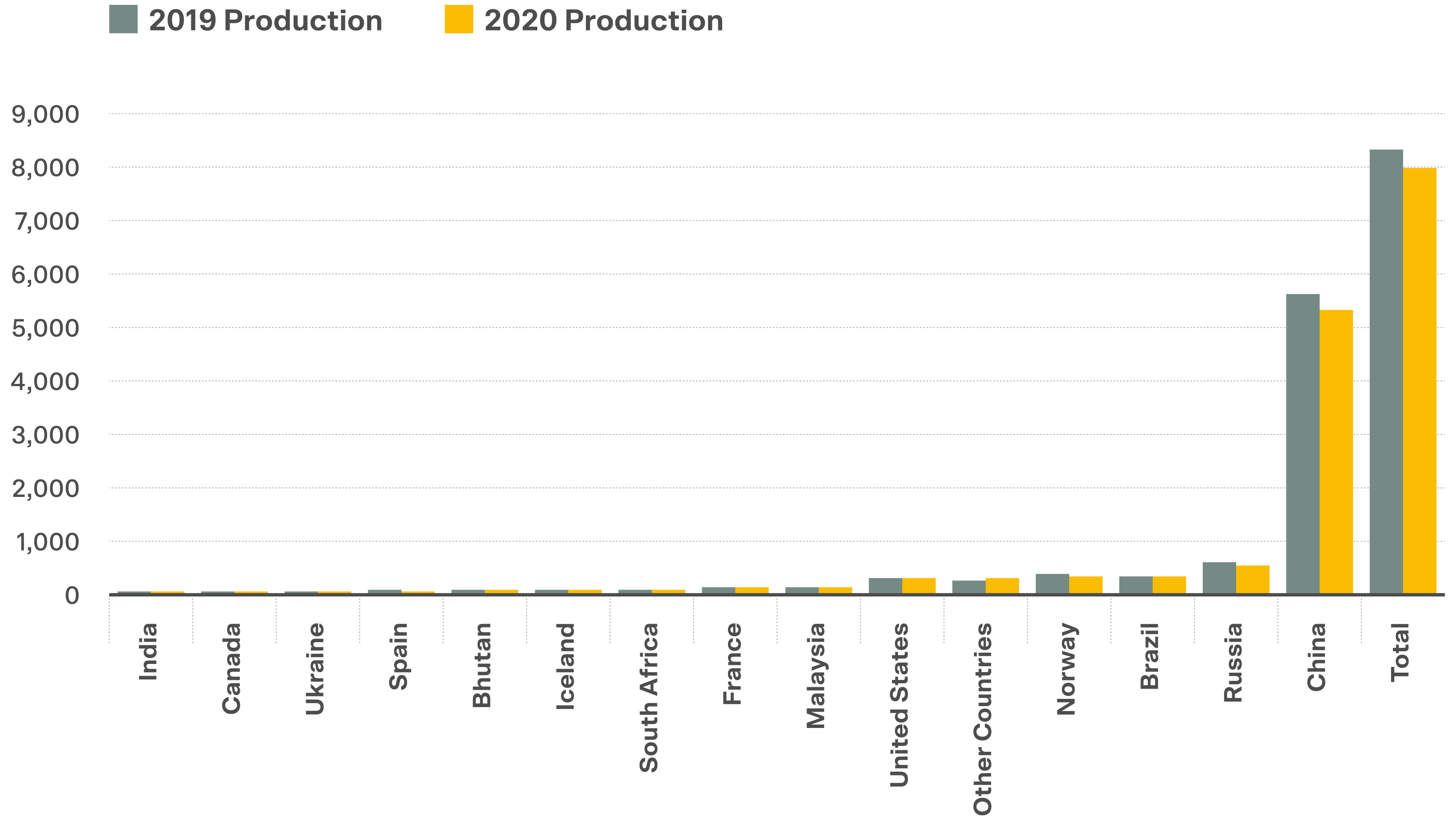

For example, the manufacturing of home electronics, digital technology, and automobiles require semiconductor chips. These, in turn, require raw materials like ferrosilicon and silicon, most of which are produced in China.

Despite decreases in total global production of ferrosilicon and silicon metals decreased between 2019 and 2020, China remained the world’s largest producer of these metals. Source: United State Geological Service, National Minerals Information Center

During the pandemic, there was a massive increase in home and workplace electronics. This in turn created an increased demand for semiconductor chips, which in turn increased the demand for silicon and ferrosilicon, the raw materials which make the chips work.

This increase in demand coupled with the decrease in supply led to a shortage of these raw materials, and an inability to produce enough semiconductors to meet the new demand for home and workplace electronics.

Furthermore, the export of these minerals was slowed as demand for masks, gowns, gloves, and other protective medical clothing and equipment skyrocketed throughout 2020.

Much of this PPC was produced in China. As China began shipping it throughout the world, not all of the shipping crates were immediately sent back. This caused empty shipping crates to began piling up at global ports far from China.

On one hand, this meant China had a shortage of shipping crates and couldn’t deliver enough goods and materials to meet demand in other nations.

On the other hand, as the crates began piling up, ships at the Port of Los Angeles, the Port of Savanah, and other major ports in the US couldn’t unload their goods for days, weeks, or even months.

Both of these events only worsened the supply chain disturbances that were already being experienced.

They also delayed the delivery of many other materials and manufactured goods including everything from toilet paper and paper towels to construction materials and real estate. The cost of many of these goods is still sky-high.

Can Joey Help Solve Supply Chain Disruptions? — A Look at Peer-to-Peer Last Mile Logistics

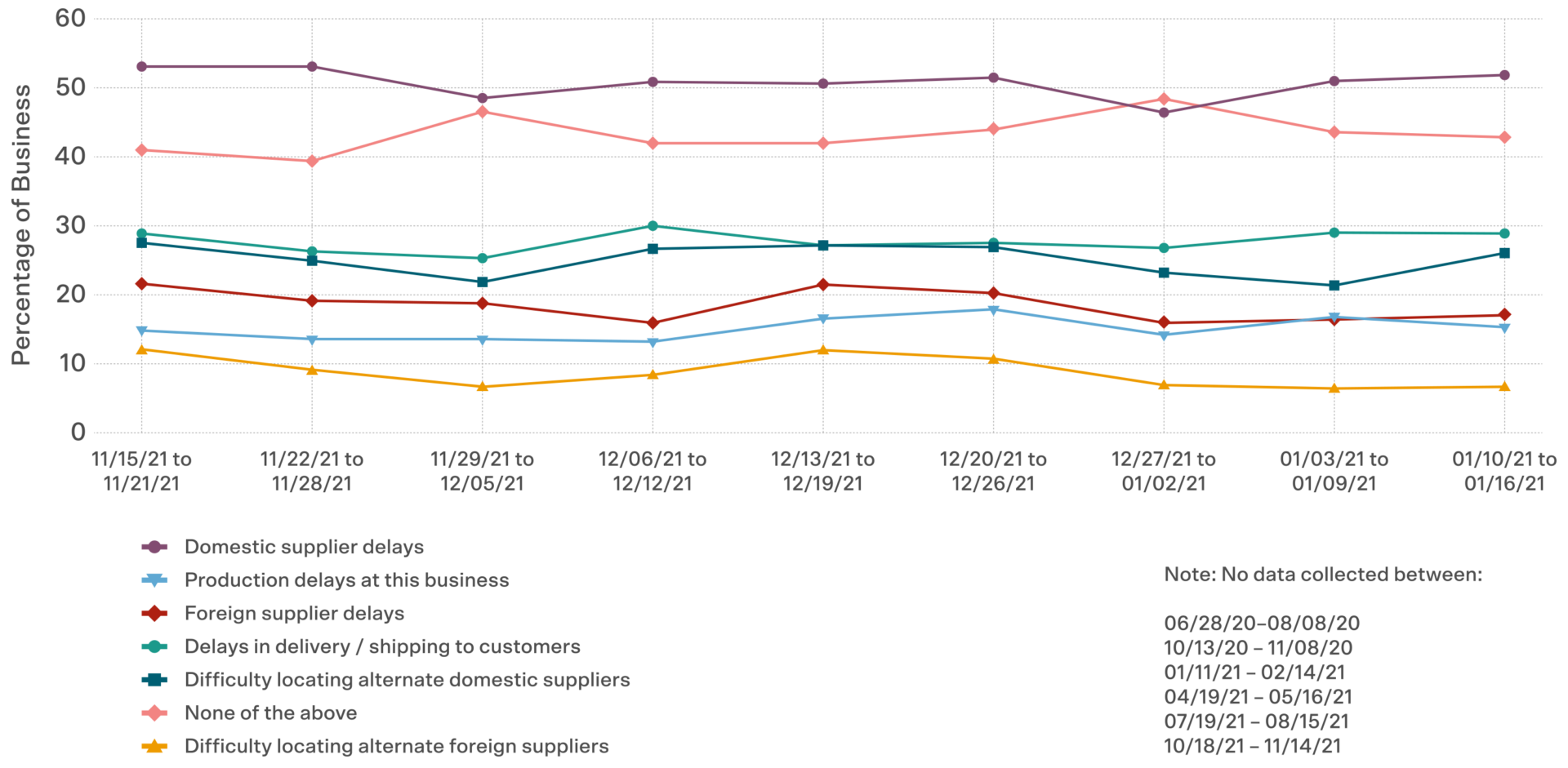

Over 25% of Ohio small businesses reported delays in delivery/shipping to customers each week between November 15, 2021, and January 16, 2022:

Over half of all small businesses in Ohio reported supply chain delays and disruptions Between November, 15 2020 and July, 16 2021. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Small Business Pulse Survey, Phase 7

Joey helps businesses and retailers solve this problem with its last-mile logistics delivery service.

Last-mile logistics refers to the final steps a package takes before reaching a customer. If you order an out-of-stock item from a local retailer, they may have it delivered to their store or local warehouse or distribution center. From there, it will be shipped to you.

The delivery distance, time, and methods that it takes for the item to enter the warehouse, be processed, and then be delivered to you are all part of last-mile logistics. Deliveries to the final customer can be delayed for all sorts of reasons.

If you’re doing in-house deliveries, perhaps you’re cutting costs by waiting to make deliveries until the truck is full, or perhaps you’re relying on the slow and delayed schedule of your local UPS or FedEx.

Whatever the reason, Joey is the alternative you’ve been looking for. With our app and desktop-based delivery platform, you can schedule a delivery with a local driver in Cincinnati, Dayton, Columbus, Louisville, or Lexington who will make sure the product gets to its final destination safely, affordably, and promptly.

— By Alexander Fred